By Nuri Kino

Tur-Abdin (Turkey) – AINA ++

The land dispute trial of St. Gabriel Monastery in Turabdin, Turkey was postponed for the fourth time. On May 6 a new court session was held in Midyat, Turkey. Again the decision was postponed, this time until May 22 and June 24.

Nuri Kino celebrates yet another Christian feast in Turabdin in south-eastern Turkey. In previous publications he has examined the trials of the Syriac Orthodox monastery of Mother Gabriel. Now he reveals that it is not only the monastery that will have their land confiscated. Many of the villages may also have their land seized by the Turkish state. And it will all be perfectly legal.

Cameras dazzle the governor, the mayor and the chief military officer in northern Mesopotamia. The sun is in full gaze. It is April 19, a hot spring day, and the Orthodox Easter Sunday. The new official face of Turkey is presented, and its representatives will visit the Syriac Orthodox Bishop Saliba ™zmen on Christianity’s most important holiday, the day of Jesus Christ’s resurrection. Everyone is welcome in the new Turkey, Christians as well as Muslims, all ethnicities and religions.

The country’s new leader’s PR machine is running smoothly. Journalists let themselves be manipulated and report to both local and national media. The following days newspapers and television channels are filled with the celebration of the Christian feast. And it is not only the photo journalists’ cameras that patter, but also the tourists’. This year, both Turkish and European tourists have found their way here early. It is the most beautiful time of the year. Mardin’s special several-thousand-year-old architecture is framed by blooming flowers, with the yellow saffron flower dominating.

Mardin has more than eighty thousand inhabitants and is the administrative capital of the province with the same name. While my taxi is driving around one of the hills of the city, I see house after house that used to belong to people I know, some of them relatives. The taxi driver asks if I have been in the town before. I can not help my sad smile. I point to the stately houses and tell of my relatives who once lived there. He asks where they are now. I reply that their children are in Istanbul and spread out over Europe, North America, the Middle East and Australia. He shakes his head and says it is sad that so few people have returned. His name is Hikmet and he is Assyrian himself. According to him, some people returned after the earthquake in western Turkey in 1999. There are now some eighty Assyrian families in Mardin, but they used to be the majority population of the city. I get off the car at the same time as the Governor and the other prominent people leave the bishop. Photographers and tourists fight to get the best picture of them.

Some hours later I am in the taxi again, now with the Swedish pastor Bertil Bengtsson and his daughter, journalist Marie Starck. We are heading to my native town Midyat and the monastery Mor (Saint) Gabriel. We make a detour to a village along the road. Here are the stories behind the camera lenses, those about persecution and oppression. Nobody is spared from the memories filled with hatred and brutal death.

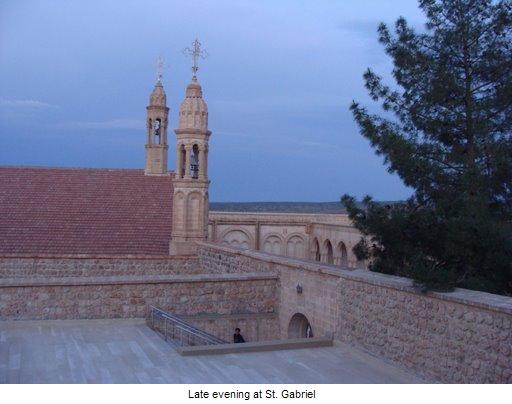

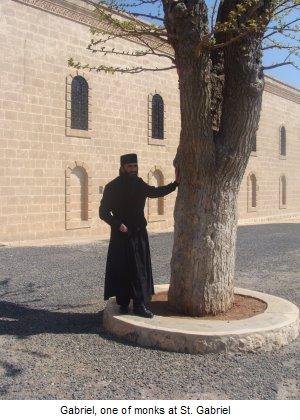

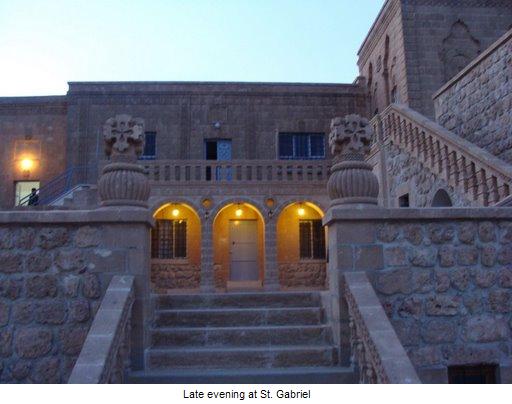

Monday, April 20 I wake up in the famous monastery. Habib, our second driver, is taking us to the cemetery. My father’s aunt has bought sweets, cheese, eggs and drinks. We are going to celebrate Easter with the locals and the dead. Priests will pray for our dead while we will compete about who has the strongest egg. We hit the eggs against each other. The person whose egg brakes has to give the weaker egg to the winner. The winning young men and women fill their pockets with eggs. We are now in Turabdin, the mountain of God’s servants, home of churches and monasteries, one of Christianity’s most sacred places. Everywhere there are Christians in beautiful clothes handing out food and sweets. Turkish journalists find it exotic. The cameras blare.

Monday, April 20 I wake up in the famous monastery. Habib, our second driver, is taking us to the cemetery. My father’s aunt has bought sweets, cheese, eggs and drinks. We are going to celebrate Easter with the locals and the dead. Priests will pray for our dead while we will compete about who has the strongest egg. We hit the eggs against each other. The person whose egg brakes has to give the weaker egg to the winner. The winning young men and women fill their pockets with eggs. We are now in Turabdin, the mountain of God’s servants, home of churches and monasteries, one of Christianity’s most sacred places. Everywhere there are Christians in beautiful clothes handing out food and sweets. Turkish journalists find it exotic. The cameras blare.

We drive away from the city and in to the villages. I am traveling with the EU official Christos Makridis, the Belgian Assyrian journalist Nail Beth-Kinne, and a middle aged couple from Austria. Our first stop is Aynward, the village in Turabdin where Christians kept up the resistance for the longest time during the genocide 1915-1920. These are new times. With new struggles. Now it’s about the land areas that are illegally confiscated by both the state and Kurdish neighbors. We visit three villages with similar stories about how the state has tricked their way to the villagers’ land. I am in Turabdin also to write about the prosecution against the St. Gabriel Monastery. In the evening we journey back to the monastery. The Bishop shows me an invitation.

On Friday the 24th of April the Interior Minister Besir Atalay will go to Turabdin to personally hand over the land registers to the villagers that previously didn’t have papers attesting that they own the land that they have inherited. The bishop is invited to participate in a ceremony that will be held in one of the Christian villages, about 50 kilometers southwest of the monastery. The official Turkey says that the minister will hand out land registers to five Christians villages and two Muslim villages that are in disputes with the state.

On Friday the 24th of April the Interior Minister Besir Atalay will go to Turabdin to personally hand over the land registers to the villagers that previously didn’t have papers attesting that they own the land that they have inherited. The bishop is invited to participate in a ceremony that will be held in one of the Christian villages, about 50 kilometers southwest of the monastery. The official Turkey says that the minister will hand out land registers to five Christians villages and two Muslim villages that are in disputes with the state.

One source tells the Turkish paper Today’s Zaman that the minister will also negotiate between the St. Gabriel monastery and those village bailiffs that claim the right to the land of the monastery. A couple phone calls later I learn that this is not true, at least to the knowledge of the inhabitants of Turabdin, neither those who still reside there nor those that have once been driven out from what used to be their homeland for thousands of years, including many who are now European citizens.

The real reason for the minister’s visit, they say, is to cover up the state’s illegal confiscation. The Turkish state has taken over land that is to a large extent owned by Assyrians. They haven’t been able to till the land for over thirty years, much because of the war between the Turkish Army and the PKK.

Since the land hasn’t been in use the state has confiscated it. Part of the land is today dominated by forest or is too stony to use for farming. Land that can’t be tilled should belong to the state, according to the law. Three quarters of many Assyrians’ property in large parts of Turabdin is about to be confiscated by the state. It is also worth mentioning that the 24th of April is the day that Assyrians, Armenians and Pontic Greeks over the world hold commemorations to acknowledge the genocide of Christians during WWI. Assyrians who lobby for the US to officially acknowledge the genocide say that the date is chosen on purpose, to take away focus from the manifestations and from Obama’s speech about the genocide on the very same day.

Tuesday morning I call the Ministry of Interior. They ask for my e-mail address. The e-mail arrives in the afternoon, and I am asked to contact Fatih Dikici. He is listed as the contact person for the Ministry of Interior. It turns out he is also one of the secretaries for the Governor of Mardin.

“I have a lot to do,” he says, “people are calling all the time. I am responsible for several delegations that are visiting the Mardin province these days.”

“When is the Minister arriving?”

“We had a minister coming recently here to visit the governor.”

“Is that the Minister of Interior?”

“No, he will arrive on the 23rd and stay until the 26th.”

“What’s the reason for his visit?”

“He will hand out land registers for seven villages, most of them Assyrian.”

“But don’t they own the land already?”

“Yes, but they don’t have the papers to prove it, these are the ones he will hand out.”

“So the reason for the Minister’s visit is that he will hand out land registers? “

“Yes.”

“Isn’t that a little bit strange?”

“No, but it’s unique.”

“Will he also visit Midyat?”

“Yes, it’s in the program. “

“Do you know what day and what time he will visit the monastery St. Gabriel?”

“He will do that after the villagers have received their land registers.”

“How many people are in the delegation?”

“About thirty.”

“Who are those?”

“Most of them are ambassadors that are stationed in Ankara, and then there are Assyrians from abroad, the Minister and his people.”

“Will the Minister also discuss the trials against St. Gabriel?”

“You know, as I said I have a lot to do. Could I call you back?”

Five minutes later he is back on the phone.

“The Minister isn’t coming.”

“No, why not?”

“I am afraid I don’t know why.”

“You haven’t been presented any reason?”

“No, we have just been told that he has to participate in something more important. But if you wait a few minutes more you will get the name of the person who will replace the Minister. “

Five more minutes later:

“Mr. Sertac S”nmezay, the deputy Chief of Staff at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will come instead. He will also stay for three days, from the 23rd to the 26th.”

“According to the paper Today’s Zaman the Minister was supposed to negotiate between the monastery and the village bailiffs. Will S”nmezay do that now?”

“You know, I am sorry but I can’t answer that question. You are welcome to e-mail me your questions and I’ll forward them to the right people.”

We finish the conversation.

A source at the District Attorney’s office in Mardin says that Sertac S”nmezay’s visit has been planned for a long time, and that among the things he will do is to review the monastery trials. In Midyat the tradition is that the Bishop celebrates Easter and Christmas in one of the city’s churches instead of in the monastery. Inhabitants of Midyat, Christians and Muslims alike, the official Turkey (the mayor and Army officers) and villagers. Everybody wants to join in and celebrate the Christian holidays with the Bishop. Villagers come and leave their gifts to show respect. Some of them later talk about their problems. I, Marie Starck and Bertil Bengtsson listen in. Almost all the villagers seem to have problem with confiscated land. A Turkish teacher who wants to remain anonymous, says:

“There is not a village in Turabdin that does not have problems. Everyone has lost land since the Kadestro law, the ten year rule, was established. The state confiscates land illegally through founding a law that gives them the right to steal. It concerns both Muslim and Christian villages, but mostly Christian.”

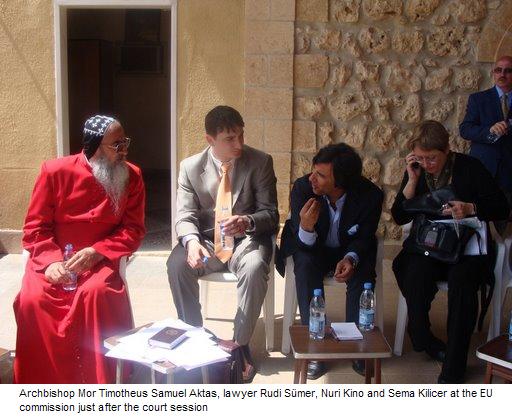

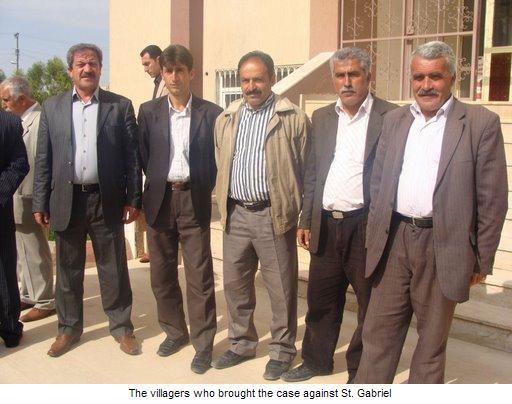

The trial takes place on Wednesday, April 22. Its the eighth round of negotiations. Some one hundred people are gathered outside the court room. Ten of them were aloud inside. Many more want to get inside. I am looking for the Muslim village bailiffs, because I want to give my condolences. They have suffered several family tragedies since I last met them. While I look around I feel a hand on my shoulder. It’s one of them, he who has lost a fourteen year old daughter. I turn around and shake his hand, and shakes the hands of his relatives and friends from the other villages. They want to talk to me after the trial.

Inside the small court room the state’s complaint against the monastery is heard first, and then the monastery’s complaint against the state. It takes about half an hour, and would have been even shorter if the printer attached to the law clerk’s computer hadn’t crashed. When the printouts are handed over to both parties a third trial is called. This one concerns the village bailiffs’ accusation that the monastery confiscates land that is considered to belong to the state, or that should be divided between the villages. The village bailiffs and their new lawyer is called to the stand. Right after we are encouraged not to cross our legs, because apparently it is not suitable in a court room.

The new lawyer lacks charisma and energy. Gone is the Ankara manner of their last lawyer. Now they have a lawyer from Midyat, a bit more cowardly, a bit slower. But you never know what hides beneath that surface. The session between the bailiffs and the monastery is over within fifteen minutes. No judgment is made, because the judge says that the lawyers are not finished with two of the investigations and thus have to wait for them to conclude. May 6 the drama will continue that has engaged thousands of people over the world. On May 22 at least three of the trials are supposed to be concluded, and the judgment will determine if the land areas inside the walls that the bishop has built belongs to the state or to the monastery.

Outside the court room one of the sons of the bailiffs is waiting for me. The cameras blare against parliamentarian Yilmaz Kerimo from Sweden, the embassy secretary of Germany, the EU commission’s secretary for Turkey and Assyrians from Europe that have come to cover the trial. The bailiffs are in the parking lot; no journalists are interested in photographing or talking with them. I once again give them my condolences. Three accidents have hit them. One where two people, a young mother and her daughter, died in a fire. Another where a teenage girl fell into a ravine and broke her neck. A third happened a couple of days before the trial, when a young man died from an electric shock.

Outside the court room one of the sons of the bailiffs is waiting for me. The cameras blare against parliamentarian Yilmaz Kerimo from Sweden, the embassy secretary of Germany, the EU commission’s secretary for Turkey and Assyrians from Europe that have come to cover the trial. The bailiffs are in the parking lot; no journalists are interested in photographing or talking with them. I once again give them my condolences. Three accidents have hit them. One where two people, a young mother and her daughter, died in a fire. Another where a teenage girl fell into a ravine and broke her neck. A third happened a couple of days before the trial, when a young man died from an electric shock.

“The women in our villages have worn black ever since we last met. It has to end. Accident after accident haunt us. Please tell them not to pray that we should be struck by accidents. It is said that St. Gabriel’s wrath has befallen us. We are just innocent farmers,” says an older man that wants to be anonymous.

The village bailiff Ismail Erkal that I visited last time I was in Turabdin is mostly quiet. He lets the other’s talk. When they have finished he takes over, he wants to speak to me in private.

“Tell the Bishop that we are tired, that neither he nor we wants this. This has cost us a lot of money ant it cost all of you that travel back and forth a lot of money and energy. Let us end this here. It is other people who are behind this whole dispute. We feel fooled and insulted. We are tired, please ask the Bishop to have an unofficial meeting with us. Negotiate between us.”

“But you testified against the monastery as late as April 4, and according to what I heard you have made new accusations against the monastery. Is that not right?”

“Yes, that’s correct. But it is not us. We are used like pawns in a game.”

I am taken aback by the village bailiffs’ words who earlier were almost fanatical in their statements against Christianity and the monastery but who now seem more like tired, fooled and suppressed farmers that have had to suffer several personal tragedies. They are ready to speak out about how it all began and what other powers have manipulated them to start these processes.

In the evening I keep my promise and talk to the Bishop. His response is that it isn’t the first time the bailiffs say that they want to solve the conflict, but that the problem is that they don’t keep their word. He wants to solve it the legal way. The monastery ‘s lawyer promised in a hearing after the court session that he would appeal to the European court if the monastery against all odds would loose in the Supreme Court in Ankara. Turkey has apparently been convicted in similar cases that Armenians and Greeks have appealed twice. But no one want it to go the Supreme Court or further, they want to solve it in Midyat — as soon as possible.

Friday April 24 I am back home in S”dert„lje, my home city that hosts twenty thousands Assyrians (who also call them themselves Syriacs and Chaldeans). I watch the evening news. Obama kept his promise, he mentioned the genocide of Christians in his speech. Though he didn’t call it genocide. He “just” said that Armenians have been massacred and deported. Assyrians over the world are happy anyway that an American president mentions the genocide on its day of acknowledgment. In my parent’s home we light a candle. On the TV I see that the Bishop Samuel Aktas was invited to hold a speech. St. Gabriel’s lawyer Rudi Smer held the speech.

While continuing watching the news I’m thinking of something a man said when I still was in Turabdin:

“But these are new times. Now blood isn’t flowing, now land is confiscated. And that according to the law. They create laws to take the last of what we have, it feels like a prolongation of the genocide,” said a German resident who was in Midyat to try to win against the state in a case concerning his father’s land that has now been confiscated by the state because it hasn’t been used in twenty years.

Three weeks ago Barack Obama finished his trip through Europe by visiting Turkey. He wanted to send a signal. He wants to see the country become a member of the EU. It has given hope to the small remaining Christian population. Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt was there at the same time I was. He also wants to see Turkey in the EU. Both government chiefs pointed out that Turkey first has to guarantee the rights of minorities.

The Turkish ruling party AKP has in the latest years placed itself in the arena of international politics through massive engagement for peace in countries like Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Syria. Nearly every day international press cameras blare against the Turkish Prime Minister, president, Minister for EU and Foreign Minister. The resurgence of the Turkish self-confidence can be felt everywhere. The American president and the Swedish prime minister’s speech and engagement to bring Turkey closer to Europe has given the country a boost.

The Turkish ruling party AKP has in the latest years placed itself in the arena of international politics through massive engagement for peace in countries like Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Syria. Nearly every day international press cameras blare against the Turkish Prime Minister, president, Minister for EU and Foreign Minister. The resurgence of the Turkish self-confidence can be felt everywhere. The American president and the Swedish prime minister’s speech and engagement to bring Turkey closer to Europe has given the country a boost.

Behind Turkey’s international engagements, president Obama’s interest for the country and Reinfeldt’s struggle for its EU membership, the cameras don’t blare. There in the dark an ugly game goes on. Yilmaz Kerimo wrote a question to Reinfeldt before the prime minister’s trip to Turkey. Kerimo wanted to know if Reinfeldt was going to raise the question about the monastery ‘s land with the Turkish government. Foreign Minister. Carl Bildt responded.

“Sweden and EU continue to take up all these questions with Turkey. For example, Sweden remains one of the driving forces to acknowledge the case with the St. Gabriel monastery. From the Swedish side we will continue to have talks with officials from the Turkish government, on different levels and in different settings, where we will push for full respect for among other things that it is necessary to respect the rights of minorities for a EU membership to be possible.”

Maybe there is hope for one of the world’s most beautiful countries. I really hope so. But first Gabriel must be left alone and the inhabitants of Turabdin that have been cheated of their land has to get redress. The Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has according to the paper Hurriyet also been involved and has said that he will follow the trials against St. Gabriel with great interest. Myself, I will also continue to investigate what happens behind the blaring cameras.

Translated from Swedish by Christopher Holmback.

Assyrian Democratic Organization ADO

Assyrian Democratic Organization ADO